Since arriving back in the UK, my EDC choices have become quite heavily restricted by British Legislation. Instead of moping around the house clutching my over-sized Cold Steels, however, I took the opportunity to go out and buy some UK legal folders instead. Now, with over a dozen knives that fit this category, I’m no longer as concerned about the legislation. While, yes, I will have plenty of knives I can really only use at home, I’m also not upset by having to carry a UK legal knife out – there are actually a lot more knives that fit into this category than you might expect.

Which brings me to the Douk-Douk. By and large, I was most surprised by the Douk-Douk in terms of overall likeability. I’ve purchased some expensive USA-made folders recently, including a Quartermaster Barney McGrew collab done with Heinnie. A sexy slab of UK legal titanium. Yet still, these days I find myself choosing to pocket the Douk-Douk over this and most other options. Less is more is an oft quoted saying, and whilst the Douk-Douk is steeped in bloody colonial history, in my hands its sober appearance and old world charm is pretty irresistible.

Douk-Douk Traditional Slip Joint Folding Pocket Knife – Amazon / Blade HQ

Douk-Douk Traditional Slip Joint Folding Pocket Knife – Amazon / Blade HQ

When thinking about inexpensive carbon steel folders from France the obvious example is the iconic Opinel. Its more famous brother has admittedly stolen most of the limelight from the Douk-Douk, though frankly I think its a shame. The Douk-Douk I am reviewing (they come in many sizes and shapes) is the standard “small” with the now famous scimitar blade and god of doom and destruction engraved on the handle (more on this later).

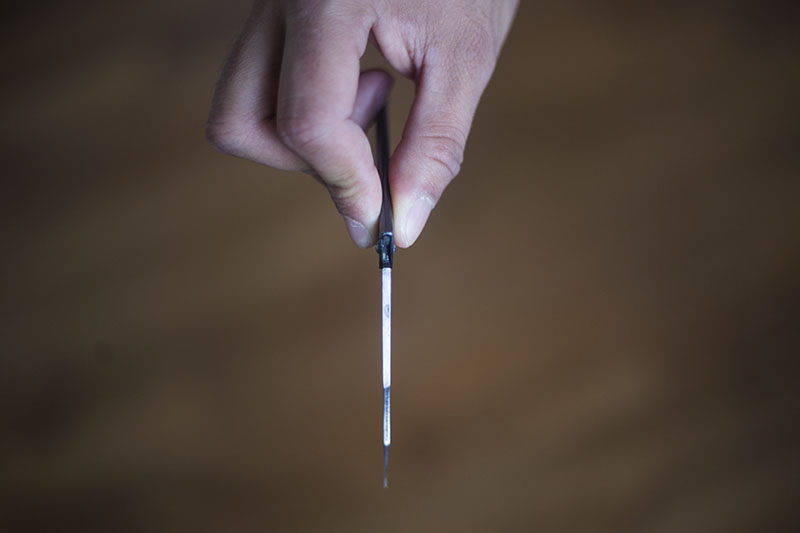

In hand, the Douk-Douk is shockingly thin. Not quite credit card thin, but pretty close for a knife.

The knife’s construction is elegantly simple. Basically a sheet of tempered steel that has been folded and ferro blackened coupled with a blade and a back spring. That’s pretty much it, and the result is a super skinny knife that, despite being 100% steel, weighs in at just 1.3 ounces. So yeah, very much on the lightweight side of things.

The blade is nicely ground from a utility point of view, but this ain’t no show queen. The machining is rough, though perfectly functional, and attention was clearly spent on performance over aesthetics.

The clip point of the 7.2 cm scimitar blade is left unfinished. Easy to finish if that’s a fix you’d like to make. The general innards are also pretty rough, at least in appearance. Functionally speaking, the Douk-Douk is very, very smooth, with a satisfying twack when the back spring engages with the blade. Surprisingly crisp, exceeding the Swiss made Victorinox Swiss Army Knives, in my experience.

The blade itself is technically just about hollow ground. Its taper is so linear that one would be mistaken for being a full flat ground in actual real world use. The steel is C75, roughly equivalent to 1074, at a hardness of around 52-54 HRC. This has been my experience when sharpening it using a waterstone.

In real world use, the Douk-Douk’s ease of sharpening is legendary and I reckon you could get a satisfactory edge using a smooth brick (I am not even joking). Getting this baby razor sharp is trivial, and whilst edge longevity does suffer compared to more modern knives, especially the ones with powder metallurgy super steels common in bleeding edge modern folders, it’s certainly not a big deal.

Strop it once in a while and it will keep trucking along.

Fit and finish is mechanically sound. Aesthetically, I personally think it’s quite charming in a rustic sort of way. Then again, I am not going to be a snob over such a traditional knife (both in design and construction) coming in at 20 bucks. It feels very nicely put together with the knife being very rigid due to its simple 3 piece construction. 2 pins keep it together and, in my experience, it has never shown any signs of developing play or any other mechanical issues.

If you feel it get loose (again, something I have not experienced), much like many Case knives, you could put it in a vise and tighten it or hit the pivot pin with a peen hammer.

The backspring is almost obscenely strong. Its not stiff the same way the Lansky World Legal is (which in my opinion is a smidgen over the top), but it’s definitely very strong. The Douk-Douk is much stronger than any Swiss Army Knife or USA-made slippie I have ever handled. I have never felt like I needed a lock with this particular knife, and the overbuilt back spring is the reason why.

No thumb nick or other opening aid is supplied. Again, this is an old school, bare bones tool designed for the colonial market, so that makes perfect sense. Not an issue for me, however, as I am rather used to being without opening aids. Some may find opening the Douk-Douk harder than opening most other slipjoints, but I cannot overstate how solid the backspring is. Frankly, handling one for yourself will give you a far better understanding of what I mean than I could ever explain.

The butt of the knife features a bail pinned into the handle. Very generous size and will support any crazy lanyard you may wish to throw on there, although personally I don’t use one. The knife’s spartan design lends it well to use with interesting cordage: from leather throngs to neon green paracord, if you are into that sort of thing!

Since the Douk-Douk is such a super thin knife, it can be carried all sorts of ways. It will fit pretty much everywhere, so for a subtle world-legal EDC, I think the Douk-Douk is pretty darn perfect. The Lanksy World Legal EDC is much bulkier, and whilst both are perfectly legal to EDC, I would argue that when speaking to a cop, it is much easier to explain that the Douk-Douk is a tool rather than a weapon than it would be to try and get away with explaining the same about a Lansky World Legal. Perception is important when dealing with authorities, in my experience. And while they can’t charge you, they certainly do have the power to confiscate knives. Speaking of which, if this gets nicked by a cop, I won’t be too sore over the loss, considering the relatively cheap cost and the fact that it’s not too hard a knife to purchase again (neither being true of my new Quartermaster/Heinnie collab knife).

As usual, the adage of “not seen, not taken” does reign supreme, and is pointedly apt in the case of the Douk-Douk being used as an EDC knife. In a situation that could turn hostile very quickly, I would say this is probably the most discreet option for a full sized pocket knife you could have. Regardless of where you live in the world.

Tell me if you ever find a full-sized knife more easy to conceal than this:

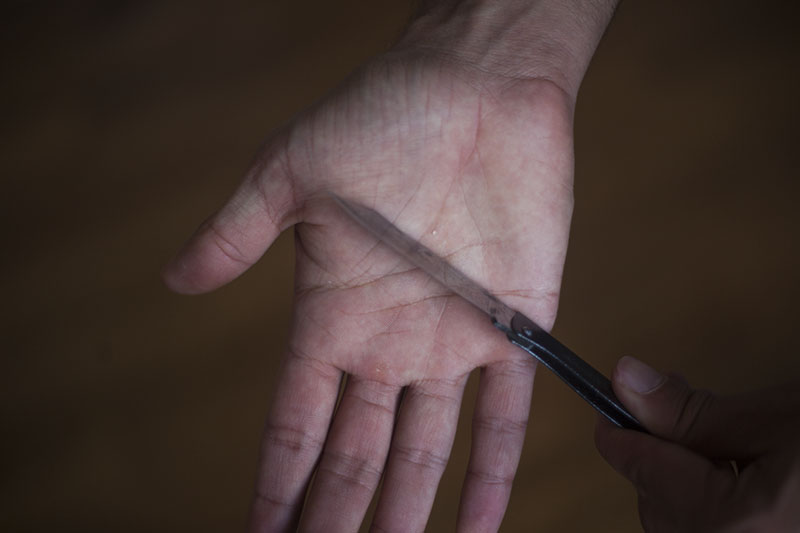

Reports of historical rebels sneaking around with the Douk-Douk in their boots during the Algerian War of Independence are rampant, and I can definitely see why! Very unobtrusive, you barely remember it’s on you, and an excellent option for a frisk-resistant last ditch option. I don’t see myself ever needing to do this, but it’s an interesting historical tidbit that it was actually carried quite frequently in the past.

With trousers over my boots, the knife is basically unnoticeable. Higher boots would make it plain invisible. I don’t EDC my knife like this, as the Douk-Douk is legal, even in my neck of the woods, and I want my primary cutting tool to be quickly and easily accessible. That being said, I would feel remiss to not mention this particular carrying method can be used quite easily with this knife. Great option as a secondary blade, if you’re ever worried about losing a knife and wanting a backup in a spot you’ll never lose it in as well.

Limited choil (of sorts). Thankfully, however, the knife has a halfway stop. Makes unlocking much easier and is a very important safety feature in slipjoint knives (in my opinion). I find it weird that a $20 knife made in the West has such a feature, but many (more expensive tools) made in the East do not, too. Function over styling to be sure – this ain’t exactly a gentleman knife, and certainly doesn’t have flourishes like inlaid scales or brass bolsters, but what it does have make perfect sense for a functional tool.

Ergonomics are…what you would expect for such an anemic knife. It’s not that it’s not comfortable, it’s just physics. You are holding a very thin handle and no matter how much time you spend contouring edges, it’s always going to be an issue if you crank out excessive torque or pressure. For its thinness, though, it’s very comfortable.

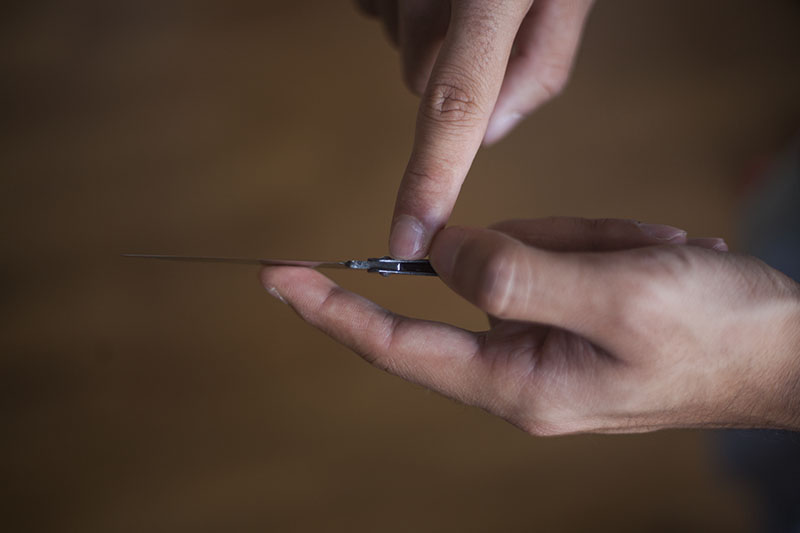

Choking up on the Douk-Douk is technically viable. My issue is not the comfort, but the safety of choking up. Despite this knife having one of the strongest springs of any slipjoint I have ever handled, it’s still a non-locking knife. Digits don’t grow back, so don’t be stupid.

As I touched on before, this is one of the few historically valid representations of a tactical knife. For those history-loving knife aficionados: you may be interested to learn that the Douk-Douk was used quite heavily in the past to assassinate people. Personally, I would not use the Douk-Douk as a dagger, simply due to my (warranted) fear of the blade folding back onto my fingers. In this day and age, we have so many superior options that it makes me uncomfortable recommending the Douk-Douk for tactical use. But it’s definitely got a rich history in that respect. Using it for anything other than light EDC these days, however, just wouldn’t make any sense.

At the same time, this knife has taken more lives than any other modern day folding knife… makes it hard for me to dispute its tactical validity completely.

Slicing is first and foremost what I associate with the Douk-Douk. Its performance is excellent and the blade being ground to such a thin edge makes using it effortless. As you can see by the discoloration and blotches on the blade, the carbon steel will rust if you look at it the wrong way. I rinse and dry it after use, but still it does end up looking this way over time. I view the patina as well deserved commendations on a sturdy tool and actually quite like it, but if you want a super pretty slip joint that has a blade that won’t stain, I would go with a Case Swayback Gent (such a lovely knife) or a Japanese-made Moki.

The Douk-Douk is a tool, not a show piece.

In doing research for this review, I read quite a bit and watched a number of videos about the Douk-Douk’s historical tactical applications. I can’t seem to find it again (if you know where this is, link the info in the comments), but somewhere on the net I came across some interesting approaches by MBC master and general old school tactical wizard Fred Perrin. He suggests holding the knife as shown below should you need to use it offensively. This allows you to be a smidgen more careless, as should the blade close, it won’t be on your fingers. With that said, I have no real opinion on the matter, considering as I’ve said, to me this wouldn’t be my first, second, or 100th choice for a folding tactical blade.

Again for the history buffs: in Northern Africa, the name “Douk-Douk” actually became synonymous with “knife” as its ubiquity spread. The knife’s use was found mostly in the French colonies of Northern Africa, but its origins are older as an inexpensive knife to be used by colonies in French Oceania. The engraving represents the Melanesian incarnation of the spirit God of death & destruction, as I mentioned in the introduction of this article. A weird selling point for an everyday tool, and whilst it didn’t carry favour with Polynesian locals who may have been quite a bit apprehensive having the god of death and destruction on their tool (go figure), it found its place amongst the other French colonies quite happily.

To this day, the Douk-Douk is still made in France in the French capital of cutlery (Thiers) by Cognet. Since 1929, they have cranked this knife out in stupendous numbers. Obvious why: it’s a really practical and interesting-looking blade to begin with; add the fact that this is probably the least expensive historical knife you could possibly own, and it becomes pretty evident how much of steal this knife is at roughly $20. Such high demand for this knife is well warranted.

To me, holding and using this knife evokes similar feelings to holding and using Case knives and Bucks.

It’s interesting to have a knife that was designed and used for a different time: where explorers still existed and the world offered uncharted danger. When a simple knife was a fearsome weapon.

These days, most knives I own are CNC-made in a factory with the design being carefully executed for a given demographic at a given price point with thousands of dollars in market research behind them. Whilst the Para-Military II is undoubtedly an excellent tool, it is very sterile and doesn’t evoke many (if any) emotions in me.

I would say this is the folding French equivalent of the American Green River knives, in terms of their ubiquity and flexible applications.

During the Algerian War, the French administration went so far as to ban this little slip joint, as it was deemed war ordinance. Its lethal applications were demonstrated by enterprising types by hammering the 2 overlaps of steel on the tips of the sheet metal handle next to the bolster that I point to in the photograph below, thus turning the knife into a quasi fixed blade.

Pretty ingenious, and whilst the lock up won’t be rock solid, it would have been highly impressive for its time. We are talking the 60s here people. The ability to turn this relatively small folding slip joint into a thin shank within 1 minute using a rock or hammer was well known, and used to great effect against colonial troops and rebels alike.

This versatility, to me, makes the Douk-Douk an interesting option as a survival blade, as the steel is so easy to sharpen, and the way you can turn it into a quasi-fixed blade has the potential to be really useful for those stuck outdoors. Is it optimal as a survival knife? Hell no, absolutely not. But for a wafer thin knife, I think it surpasses most (if not all) survival tin knives. I think it’s a great option for a backup blade, even in the outdoors. As I’ve already said, you could keep it in your boot and not notice it at all. Very handy in case you ever happen to lose your backpack or your main knife: at least you won’t be left with nothing (unless somehow your boots magically drift away, too).

For a knife with a reputation for being a lil’ rough and ready, I do think the Douk-Douk is pretty. The ferro blackened handle (an old Gunsmithing technique) is unique in its luster. Certainly, many may not want to go so far as to call it beautiful (Elise insists she would), but I think we can all agree that it’s quite a special little tool.

Knives are one of mankind’s oldest tools, and when I handle a Douk-Douk, I feel this quite vividly.

The Douk-Douk is not only a tool, it’s also part of our shared human heritage, much like the Buck 110 and the Opinel. Whilst this is an emotional argument in favour of this knife, that doesn’t discount in any way the viability of the Douk-Douk as a great everyday carry option. It is still, to this day, an excellent (very) thin EDC, with a very utilitarian blade grind and good, all-around steel. Plus, it’s legal to carry pretty much everywhere in the world, and at such a low price point, I think it deserves to be in everyone’s collection.

I often find myself at a crossroads when reviewing knives of such stature because so much of the appeal is rooted in history. If someone created this knife today, I wouldn’t recommend it based on cost and finish. I would definitely be a lot harsher with my criticisms. Through the lens of history, however, I can appreciate the Douk-Douk’s rough edges and lower hardness carbon steel, especially as it’s still made by the same company as it was in the 1930s. I had similar argument in favour of the Buck 110, and I think they apply here, too. If you dig knife history at all, this is a unique, inexpensive folder that is super for its time, and honestly has withstood the test of time in terms of everyday carry viability.

Very good review which brings out both the allure & practicality of the Douk-Douk, it certainly is a credible carry and highly useful outdoors tool. I like the small sized model, 9cm as it truly disappears with carry but the very strong backspring and minimalism /simplicity of construction mean it is no pretender or outdated relic. Have both the Carbon version with blued handle and the Stainless one which I actually prefer for ease of outdoor use- corrosion issues- plus it’s a very tidy food prep knife. The handle is chromed nickel and the blade Sandvik 14c28n- don’t know what the hardness is but estimate 58, it sharpens very nicely indeed and like a lot of French spring knives it opens quite easily but is quite hard to close(as it should be) it also has ‘talk’ and a satisfying whack when shut. Unlike many French Traditional knives, it has a kick so there’s no risk of blade rap when you slam it shut from the half-stop position.

It’s a surprising and delightful carry and being inexpensive gives it an honest appeal too. Think all enthusiasts, outdoors types or collectors should have one, they’re a fine addition and rewarding to use.

I would like to know what You think about the Böker Atlas (or Sanrenmu PT721). Because You liked Petit Douk-Douk would You consider this Böker a similar knife as in terms of sturdiness, durability and usage?

I have a trouble which one to choose. Douk-Douk seems to be a great heritage knife but Böker still is on my mind…

I love them! I own 2, brass and copper. Really great knives and very durable. Similar size to the douk-douk but due to modern materials, its far more durable. They also have a pocket clip which makes hell of a difference in usability.

I think that I had heard the name once or twice before I saw Knife Center offering one for $45. I am leery of buying a knife without knowing the name of the steel. You provided that. I read the review out of curiosity. It has not inspired me to purchase one, but I was very impressed with the work that wen into this and the excellence of the product. Thank you.

Yeah, the douk-douk is more of a historical curiosity than a comparable EDC knife by modern standards so I completely get it. ;)

I love mt Douk-Douk too, as you say a nice tool with a rich history.

In reply to Gordon; very few knives are actually banned out-right in the UK, flick knives, punch daggers, butterfly knives and sword-sticks spring to mind, but everything else is legal to own.

“UK legal” is often used to cover the sort of knives allowed to be carried in public with out “a valid reason” (eg a Chef taking their knives to work) Sub 3″ non locking folders are ok to carry everywhere (except sports matches, schools ad courts) If you want to carry anything else you need a reasonable excuse for it.

Having a filleting knife in the bottom of your fishing tackle box while driving to the lakes would be ok; saying you have a filleting knife in your glove box because you are a fisherman….less so.

While not perfect I have not found any EDC task that can’t be done with a UK legal carry blade, and if I need a locking or fixed blade I will have a good reason for it.

This.

Whilst I despise the regulation I am inclined to agree that I never feel like I *need* a locking blade for regular EDC. In the outdoors I am perfectly entitled to carry by new Tops Lite Trekker so my life hasn’t changed much from my move to the UK in terms of the tools I need.

Are you still able to collect knives like you did before moving to England?

Yup, no problems buying whatever I want (except for Auto’s and Balis but then again I couldn’t buy those in Canada either).

Ownership is legal, use on private property is legal, use on public property as long as you have a valid reason is legal (bushcraft knife when bushcrafting is fine).

EDC of locking knives is where the issue lies.